COLOUR TEMPERATURE

The colour of the light we use has a direct effect on our photographs. But there’s no need to get bogged down with technicalities to make the most of this colour temperature.

An understanding of the colour, or temperature, of light is essential if you want to get the most from every subject and all situations. Not least because when you understand what’s going on you can take steps to avoid simple mistakes. It will also open up the most wonderful opportunities for capturing and emphasising colours in situations when you might otherwise be tempted to put away your camera.

WARM IT UP

In the days of film, we often had to put a ‘warm-up’ filter over our lens. These 81 series filters were tinted slightly amber in colour and took away the blue cast in a picture taken on an overcast, cloudy day. That’s because our Daylight colour film was formulated to produce correct colours – whites as pure white etc – on a sunny day with a few puffy clouds in the sky. Now, with digital, all we need do is adjust our White Balance (WB) setting. It’s great, we even have the luxury of Auto White Balance (AWB). This acts like a sliding scale, correcting a little too much blue or too much yellow in the light either side of ‘daylight’. AWB is not the answer to everything, but it’s good.

SHOOTING RAW?

Of course, many photographers now shoot RAW files, and these images are then corrected in post processing. Here I am talking about setting the camera to shoot JPEG files, and with these, colour corrections are made, mostly, in the camera when the picture is taken.

WHAT’S HOT?

You’ll notice that what we naturally think of as ‘cold’, blue light is, in photographic terms, high temperature light on the Kelvin Scale. What people normally think of as ‘warm’ golden light (the golden light from tungsten light bulbs, candles etc.), is in fact low temperature light. A tungsten light bulb is around 2,500K. Unless you adjust your WB setting to Tungsten – that’s usually indicated by the little icon of a light bulb, or take a Custom WB setting, pictures taken in the light of ordinary light bulbs will have a yellow colour cast.

KELVIN SCALE

The colour (temperature) of light is measured on the Kelvin Scale, and our Daylight colour film was formulated to produce correct colours at around 5,500K (Kelvin). The same principle applies to our digital cameras. When the sky clouds over the temperature of the light actually goes up the Kelvin Scale. Maybe to around 6,500K. In deep shade on a sunny day the light can be very blue indeed – very high colour temperature. Perhaps about 10,000K or more.

Don’t panic! You don’t need to remember these numbers, but they do give you an idea of what’s going on. When you know what’s happening, you can use these different colours of light to create the most beautiful effects – and you can often change things by taking control of your WB settings on the camera. Understanding colour temperature opens up the most wonderful picture opportunities.

MIXING COLOUR TEMPERATURES

MAGAZINE DEADLINE

Knowing how to use colour temperature can often save the day for a professional photographer. I was sent by The Times Magazine to photograph Newlyn in Cornwall. A tight deadline meant I had just one day to do the pictures. My brief was for a couple of very colourful pictures. It rained solidly all day and colour was in very short supply. When the rain stopped just before darkness, I quickly set about getting my first colourful picture – using the blue light of dusk mixed with the golden light of a floodlight at the end of the pier.

So I had one picture, but needed another. It was now dark, but I knew I would have a second bite at the Mixed Light cherry – before dawn. That night in the darkness, I dragged the lobster pot into a position beneath the harbour light ready for morning. I was back on the quayside well before dawn. The lobster pot was lit with a flash from the side. A long exposure captured the low temperature glow of the harbour lights and the high temperature blue light of the pre-dawn sky.

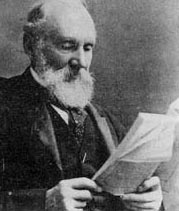

William Thompson, Lord Kelvin 1824-1907

Next time you set the ‘cloudy’ or ‘light bulb’ icon on your WB settings, spare a thought for Lord Kelvin, he was quite a man. Kelvin not only quantified the Kelvin Scale of absolute temperature, he was a Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at Glasgow University. This man developed the science of thermodynamics, invented the mirror galvanometer, a telegraph message receiver, and supervised the laying of the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cable. He published 660 scientific papers, the first at the age of 16. Lord Kelvin was a champion rower and founded Glasgow University Music Society.

Kelvin was knighted in 1866 and created Baron Kelvin of Largs in 1892. He is buried in Westminster Abbey.

This article, written and photographed by Philip Dunn, first appeared in Amateur Photographer Magazine